Treasure Island

| Treasure Island! (novel) | |

|---|---|

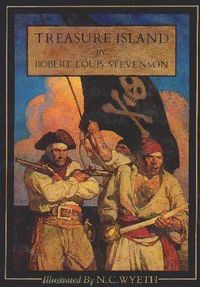

Cover illustration from 1911 |

|

| Author | Robert Louis Stevenson |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Adventure, Young Adult Literature |

| Publisher | London: Cassell and Company (Now part of Orion Publishing Group) |

| Publication date | 1883 |

Treasure Island is an adventure novel by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, narrating a tale of "pirates and buried gold". First published as a book in 1883, it was originally serialized in the children's magazine Young Folks between 1881-82 under the title The Sea Cook; or, Treasure Island: A Story for Boys.

Traditionally considered a coming-of-age story, it is an adventure tale known for its atmosphere, character and action, and also a wry commentary on the ambiguity of morality—as seen in Long John Silver—unusual for children's literature then and now. It is one of the most frequently dramatised of all novels. The influence of Treasure Island on popular perception of pirates is vast, including treasure maps with an "X", schooners, the Black Spot, tropical islands, and one-legged seamen with parrots on their shoulders.

Contents |

History

Stevenson was 30 years old when he started to write Treasure Island, and it would be his first success as a novelist. The first fifteen chapters were written at Braemar in the Scottish Highlands in 1881. It was a cold and rainy late-summer and Stevenson was with five family members on holiday in a cottage. Young Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson's stepson, passed the rainy days painting with watercolours.[1][2] Remembering the time, Lloyd wrote:

| “ | ... busy with a box of paints I happened to be tinting a map of an island I had drawn. Stevenson came in as I was finishing it, and with his affectionate interest in everything I was doing, leaned over my shoulder, and was soon elaborating the map and naming it. I shall never forget the thrill of Skeleton Island, Spyglass Hill, nor the heart-stirring climax of the three red crosses! And the greater climax still when he wrote down the words "Treasure Island" at the top right-hand corner! And he seemed to know so much about it too — the pirates, the buried treasure, the man who had been marooned on the island ... . "Oh, for a story about it", I exclaimed. ... .[3] | ” |

Within three days of drawing the map for Lloyd, Stevenson had written the first three chapters, reading each aloud to his family who added suggestions. Lloyd insisted there be no women in the story which was largely held to with the exception of Jim Hawkins' mother at the beginning of the book. Stevenson's father took a child-like delight in the story and spent a day writing out the exact contents of Billy Bones's sea-chest, which Stevenson adopted word-for-word; and his father suggested the scene where Jim Hawkins hides in the apple barrel. Two weeks later a friend, Dr. Alexander Japp, brought the early chapters to the editor of Young Folks magazine who agreed to publish each chapter weekly. Stevenson wrote at the rate of a chapter a day for fifteen days straight, then ran dry of words, partly due to his health. He had never earned his keep by age thirty-one, and was desperate to finish the book. He turned to the proofs, corrected them, took morning walks alone, and read other novels.

As autumn came to Scotland, the Stevensons left their summer holiday retreat for London, and Stevenson was troubled with a life-long chronic bronchial condition. Concerned about a deadline they travelled in October to Davos, Switzerland where the break from work and clean mountain air did him wonders, and he was able to continue at the rate of a chapter a day and soon finished the storyline.

During its initial run in Young Folks from October 1881 to January 1882, Treasure Island failed to attract attention or even increase the sales of the magazine, but when sold as a book in 1883 it soon became very popular.[4] The Prime Minister, Gladstone, was reported to have stayed up until two in the morning to finish it. Critics widely praised it. American novelist Henry James praised it as "perfect as a well-played boy's game".[5] Gerard Manley Hopkins wrote "I think Stevenson shows more genius in a page than Sir Walter Scott in a volume". Stevenson was paid 34 pounds seven shillings and sixpence for the serialization and 100 pounds for the book.

Thanks to Stevenson's letters and essays, we know a great deal about his sources and inspirations. The initial catalyst was the island map, which was essentially the whole plot to him as author, he said. He mailed the map with his manuscript to the book publisher and was later told the map had been lost. He had no copy and was devastated. To Stevenson, the map he tediously reconstructed from memory and reference to the text was never the real Treasure Island. The novel also drew from memories of works by Daniel Defoe, Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug", and Washington Irving's "Wolfert Webber", of which Stevenson said, "It is my debt to Washington Irving that exercises my conscience, and justly so, for I believe plagiarism was rarely carried farther.. the whole inner spirit and a good deal of the material detail of my first chapters.. were the property of Washington Irving."[6] The novel At Last by Charles Kingsley was also a key inspiration.

The character of Long John Silver was inspired by his real-life friend William Ernest Henley, a writer and editor, who had lost his lower leg to tuberculosis of the bone. Lloyd Osbourne described him as "..a great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one's feet". In a letter to Henley after the publication of Treasure Island, Stevenson wrote "I will now make a confession. It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver...the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you".

Stevenson had never encountered real pirates: the "Golden Age of Piracy" had ended more than a century before he was born. However, his descriptions of sailing and seamen and sea life are very convincing. His father and grandfather were both lighthouse engineers and frequently voyaged around Scotland inspecting lighthouses, taking the young Robert along. Two years before writing Treasure Island he had crossed the Atlantic Ocean. So authentic were his descriptions that in 1890 William Butler Yeats told Stevenson that Treasure Island was the only book from which his seafaring grandfather had ever taken any pleasure.[7]

"The effect of Treasure Island on our perception of pirates cannot be overestimated. Stevenson linked pirates forever with maps, black schooners, tropical islands, and one-legged seamen with parrots on their shoulders. The treasure map with an X marking the location of the buried treasure is one of the most familiar pirate props",[8] yet it is entirely a fictional invention which owes its origin to Stevenson's original map. The term "Treasure Island" has passed into the language as a common phrase, and is often used as a title for games, rides, places, etc.

Plot summary

The novel is divided into 6 parts and 34 chapters: Jim Hawkins is the narrator of all these except for chapters 16-18 which are narrated by Doctor Livesey.

The novel opens in a seaside village in south-west England in the mid-18th century. The narrator, Jim Hawkins, is the young son of the owners of the Admiral Benbow Inn. An old drunken seaman named Billy Bones becomes a long-term lodger at the inn, only paying for about the first week of his stay. Jim quickly realizes that Bones is in hiding, and that he particularly dreads meeting an unidentified seafaring man with one leg. Some months later, Bones is visited by a mysterious sailor named Black Dog. Their meeting turns violent, Black Dog flees, and Bones suffers a stroke. While Jim cares for him, Bones confesses that he was once the mate of the late notorious pirate, Captain Flint, and that his old crewmates want Bones's sea chest.

Some time later, another of Bones's crewmates, Pew, appears at the inn and forces Jim to lead him to Bones. Pew gives Bones a paper. After Pew leaves, Bones opens the paper to discover the Black Spot, a pirates' summons, with the warning that he has until ten o'clock, and he drops dead of apoplexy (in this context, a stroke) on the spot. Jim and his mother open Bones' sea chest to collect the amount due for Bones's room and board, but before they can count out the money that they are due, they hear pirates approaching the inn and are forced to flee and hide, Jim taking with him a mysterious oilskin packet from the chest. The pirates, led by Pew, find the sea chest and the money, but are frustrated that the chest does not contain "Flint's fist." Revenue agents approach and the pirates escape to their vessel, except for blind Pew, who is accidentally run down and killed by the agents' horses[9].

Jim takes the mysterious oilskin packet to Dr. Livesey, as he is a "gentleman and a magistrate", and he, Squire Trelawney and Jim Hawkins together examine, finding a logbook detailing the treasure looted during Captain Flint's career, and a detailed map of an island, with the location of Flint's treasure caches marked on it. Squire Trelawney immediately plans to outfit a sailing vessel to hunt the treasure down, with the help of Dr. Livesey and Jim. Livesey warns Trelawney to be silent about their objective.

Going to Bristol, Trelawney buys a schooner named Hispaniola, hires a Captain Smollett to command her, and retains Long John Silver, owner of "The Spy-glass" tavern and a former sea cook, to run the galley. Silver helps Trelawney to hire the rest of his crew. When Jim comes to Bristol and visits Silver at the Spy Glass tavern, his suspicions are immediately aroused: Silver is missing a leg, like the man Bones warned about, and Black Dog is sitting in the tavern. Black Dog runs away at the sight of Jim, and Silver denies all knowledge of the fugitive so convincingly that he wins Jim's trust.

Despite Captain Smollett's misgivings about the mission and Silver's hand-picked crew, the Hispaniola sets sail for the Caribbean Sea. As they near their destination, Jim crawls into the ship's apple barrel to get some apples. While inside, he overhears Silver talking secretly with some of the other crewmen. Silver admits that he was Captain Flint's quartermaster and that several of the other crew were also once Flint's men, and he is recruiting more men from the crew to his own side. After Flint's treasure is recovered, Silver intends to murder the Hispaniola's officers, and keep the loot for himself and his men. When the pirates have gone back to their berths, Jim warns Smollett, Trelawney, and Livesey of the impending mutiny.

When they reach Treasure Island, the bulk of Silver's men go ashore immediately. Although Jim is not yet aware of this, Silver's men have given him the Black Spot and demanded to seize the treasure immediately, discarding Silver's own more careful plan to postpone any open mutiny or violence until after the treasure is safely aboard. Jim lands with Silver's men, but runs away from them almost as soon as he is ashore. Hiding in the woods, Jim sees Silver murder Tom, a crewman loyal to Smollett. Running for his life, he encounters Ben Gunn, another ex-crewman of Flint's who has been marooned three years on the island, but who treats Jim kindly in return for a chance of getting back to civilization.

In the meanwhile, Trelawney, Livesey, and their men surprise and overpower the few pirates left aboard the Hispaniola. They row to shore and move into an abandoned, fortified stockade on the island, where they are soon joined by Jim Hawkins, having left Ben Gunn behind. Silver approaches under a flag of truce and tries to negotiate Smollett's surrender; Smollett rebuffs him utterly, and Silver flies into a rage, promising to attack the stockade. "Them that die'll be the lucky ones," he threatens as he storms off. The pirates assault the stockade, but in a furious battle with losses on both sides, they are worsted and driven off.

During the night, Jim sneaks out of the stockade, takes Ben Gunn's coracle and approaches the Hispaniola under cover of darkness. He cuts the ship's anchor cable, setting her adrift and out of reach of the pirates on shore. After daybreak, he manages to approach the schooner again and board her. Of the two pirates left aboard, only one is still alive: the coxswain, Israel Hands, who has murdered his comrade in a drunken brawl, and been badly wounded in the process himself. Hands agrees to help Jim helm the ship to a safe beach in exchange for medical treatment and brandy, but once the ship is approaching the beach, Hands tries to murder Jim. Jim escapes him by climbing the rigging, and when Hands tries to skewer him with a thrown dirk, Jim reflexively shoots Hands dead.

Having beached the Hispaniola securely, Jim returns to the stockade under cover of night and sneaks back inside. Because of the darkness, he does not realize until too late that the stockade is now occupied by the pirates, and he is easily captured. Silver, whose always-shaky command has become more tenuous than ever, seizes on Jim as a hostage, refusing his men's demands to kill him or torture him for information.

Silver's rivals in the pirate crew, led by George Merry, again give Silver the Black Spot and move to depose him as captain. Silver answers his opponents eloquently, rebuking them for defacing a page from the Bible to create the Black Spot and reveals that he has obtained the map to the treasure from Dr. Livesey, thus restoring the crew's confidence in him. The following day, the pirates search for the treasure. They are shadowed by Ben Gunn, who makes ghostly sounds to dissuade them from continuing, but Silver forges ahead and locates the place where Flint's treasure was buried. The pirates discover that the cache has been rifled and all of the treasure is gone.

The enraged pirates turn on Silver and Jim, but Ben Gunn, Dr. Livesey and Abraham Gray attack the pirates by surprise, killing two and dispersing the rest. Silver surrenders to Dr. Livesey, promising to return to his duty. They go to Ben Gunn's cave home, where Gunn has had the treasure hidden for some months. The treasure is divided amongst Trelawney and his loyal men, including Jim and Ben Gunn, and they return to England, leaving the surviving pirates marooned on the island. Silver escapes with the help of the fearful Ben Gunn and a small part of the treasure. Remembering Silver, Jim reflects that "I dare say he met his old Negress [wife], and perhaps still lives in comfort with her and Captain Flint [his parrot]. It is to be hoped so, I suppose, for his chances of comfort in another world are very small."

Captain Flint backstory

Treasure Island contains numerous references to fictional past events, gradually revealed throughout the story and yielding a backstory that sheds light upon the events of the main plot.

The bulk of this backstory concerns the pirate Captain J. Flint, "the bloodthirstiest buccaneer that ever lived", who never appears, being dead before the main story opens. Flint was captain of the Walrus, with a long career, operating chiefly in the West Indies and the coasts of the southern American colonies. His crew included the following characters who also appear in the main story: Flint's first mate, William (Billy) Bones; his quartermaster John Silver; his gunner Israel Hands; and among his other sailors: George Merry, Tom Morgan, Pew, "Black Dog" and Allardyce (who becomes Flint's "pointer" toward the treasure). Many other former members of Flint's crew were on the cruise of the Hispaniola, though it is not always possible to identify which were Flint's men and which later agreed to join the mutiny—-such as the boatswain Job Anderson and a mutineer "John", killed at the rifled treasure cache.

Flint and his crew were successful, ruthless, feared ("the roughest crew afloat"), and rich, if they could keep their hands on the money they stole. The bulk of the treasure Flint made by his piracy—-£700,000 worth of gold, silver bars and a cache of armaments—-was, however, buried on a remote Caribbean island. Flint brought the treasure ashore from the Walrus with six of his sailors, also building a stockade on the island for defence. When they had buried it, Flint returned to the Walrus alone-—having murdered all of the other six. A map to the location of the treasure he kept to himself until his dying moments.

The whereabouts of Flint and his crew are obscure immediately thereafter, but they ended up in the town of Savannah, Province of Georgia. Flint was then ill, and his sickness was not helped by his immoderate consumption of rum. On his sickbed, he was remembered for singing the chantey "Fifteen Men" and ceaselessly calling for more rum, with his face turning blue. His last living words were "Darby M'Graw! Darby M'Graw!", and then, following some profanity, "Fetch aft the rum, Darby!". Just before he died, he passed on the treasure map to the mate of the Walrus, Billy Bones (or so Bones always maintained).

After Flint's death, the crew split up, most of them returning to England. They disposed of their shares of the unburied treasure diversely. John Silver held on to £2,000, putting it away safe in banks—and became a waterfront tavern keeper in Bristol, England. Pew spent £1,200 in a single year and for the next two years afterwards begged and starved. Ben Gunn returned to the treasure island to try to find the treasure without the map, and as efforts to find it immediately failed, his crew mates marooned him on the island and left. Bones, knowing himself to be a marked man for his possession of the map (as soon as the other members of Flint's crew should desire to recover the treasure), looked for refuge in a remote part of England. His travels took him to the rural West Country seaside village of Black Hill Cove and the inn of the 'Admiral Benbow'.

Main characters

- Jim Hawkins: the boy who finds the treasure map; he is the protagonist and chief narrator. His parents are the owners of "The Admiral Benbow Inn."

- Billy Bones: ex-mate of Captain Flint's ship and possessor of the map of Treasure Island. Dies of a stroke brought on by a combination of alcoholism and fear when "tipped" the Black Spot.

- Squire John Trelawney: a skilled marksman, he is naïve and hires the crew almost entirely on Long John Silver's advice. He has some sea-going experience and sometimes stands watch in calm weather. His propensity to talk too much is nearly the downfall of the expedition.

- Dr. Livesey: a doctor, magistrate, former soldier (having served under the Duke of Cumberland) and friend of Trelawney who goes on the journey and for a short while narrates the story.

- Captain Alexander Smollett: the stubborn, but loyal, captain of the Hispaniola.

- Long John Silver: formerly Flint's quartermaster, later leader of the Hispaniola's mutineers. Engaged as the ship's cook, and formerly the quartermaster on Flint's ship. Seemingly respectable in the beginning, he is landlord of "The Spy-glass" public house. Throughout the novel it is made clear that Silver is a remarkably charming man, whom even his enemies can't quite dislike. It is also clear that he is intelligent, ruthless, manipulative, and without a conscience.

- Israel Hands: ship's coxswain and Flint's ex-gunner; tries to kill Jim Hawkins and ends up in Davy Jones' Locker. The character may have been named for the real-life pirate Israel Hands.

- Ben Gunn: a half-insane and marooned ex-pirate, who becomes a lodge keeper after losing his share of the treasure; speaks in a "rusty voice" and craves toasted cheese. He has already found and removed the treasure before the events of the story.

- Pew: a blind ex-pirate (used to be part of Flint's crew), now beggar and killer, who dies when he is trampled by horses. With Pew and Long John Silver, Stevenson sought to avoid predictability by making the two most dangerous characters in Treasure Island a blind man and an amputee. Stevenson also introduced a dangerous blind man in Kidnapped.

- Captain Flint: a feared pirate captain who dies in Savannah from rum; also the name of Long John's parrot.

Other characters

- Mr. and Mrs. Hawkins, the parents of Jim Hawkins

- Black Dog, one of the companions of Pew who visit the Spyglass Inn (used to be part of Flint's crew)

- Tom Redruth: The gamekeeper of Squire Trelawney, accompanies him to the island, ends up being shot and killed by the mutineers before the attack on the stockade

- Richard Joyce: One of the manservants of Squire Trelawney, accompanies him to the island, is later shot through the head and killed by a mutineer at the attack on the stockade

- John Hunter: the other manservant of Squire Trelawney, accompanies him to the island, is later knocked unconscious at the attack on the stockade. He then dies of his injuries while unconscious

- Abraham Gray: A ship's carpenter on the Hispaniola. He is almost incited to mutiny but later defects to the other side when asked to do so by Captain Smollett. Saves Hawkins life by killing Job Anderson at the attack on the stockade, helps shoot the mutineers at the rifled treasure cache. Later escapes the island along with Jim Hawkins, Dr. Livesey, Squire Trelawney, Captain Smollett, Long John Silver and Ben Gunn. Spends his part of the treasure on his education, marries, then becomes part owner of a full rigged ship

- Tom Morgan: an ex-pirate from Flint's old crew; ends up being marooned on the island

- Job Anderson: ship's boatswain and one of the leaders of the mutiny who is killed while trying to storm the blockhouse; possibly one of Flint's old pirate hands

- John: a mutineer who is injured while trying to storm the boathouse, later shown with a bandaged head, ends up being killed at the rifled treasure cache; possibly one of Flint's old pirate hands

- O'Brien: a mutineer who survives the attack on the boathouse and escapes, but is later killed by Israel Hands in a drunken fight on the Hispaniola; possibly one of Flint's old pirate hands.

- Dick: a mutineer who has a Bible. The pirates later use one of its pages to make a Black Spot. Dick later ends up being marooned on the island after the deaths of George Merry and John.

- Mr. Arrow: The first mate of the Hispaniola. He drinks alcohol even though there was a rule about no alcohol on board and is useless as an officer. He mysteriously disappears before they get to the island and his position is filled by Job Anderson.

- Tom: A sailor who does not defect to mutiny. He hears the dying scream of Alan, and decides to stay honest. He starts to walk away from Long John Silver and the mutineer throws his crutch, breaking Tom's back. Silver then kills Tom by stabbing him twice.

- Alan: A sailor who does not defect to mutiny. He is killed by the mutineers for his loyalty and his dying scream is heard by several of the others.

- Additionally, there are minor characters whose names are not revealed. Some of those are the four pirates who were killed at the attack on the stockade along with Job Anderson, the pirate who was killed by the honest men minus Jim Hawkins before the attack on the stockade, the pirate who was shot by Squire Trelawney (who was aiming at Israel Hands) and later died of his injuries, and the pirate who was marooned on the island along with Tom Morgan and Dick

Themes and conflicts

One of the principal conflicts in Treasure for Island is between the virtue of advanced civilization versus the indiscipline of man in his savage state. Jim Hawkins, Dr. Livesey, and Captain Smollett, among the principal heroes, stand for virtues such as loyalty, truthfulness, thrift, discipline, religious faith, and temperance (especially with alcohol). The pirates suffer from drunkenness, impiety, and mutual betrayal, and tend to seize immediate gratification on the premise that life is short and uncertain. Long John Silver occupies a middle ground in this conflict: he shares the heroes' virtues of temperance, thrift, and deferred gratification, but only to aid him in achieving his ends, for which he is also willing to lie, betray, and murder. Most of the pirates can not even achieve Long John's level, which gives him a natural advantage in their company.

Truthfulness and loyalty

The novel can be seen as a bildungsroman, dealing, as it does, with the development and coming-of-age of its narrator, Jim Hawkins. Jim's moral development culminates when he promises Silver not to attempt an escape, and then meets with Dr. Livesey at the edge of the stockade. Jim, fearing that he may divulge the Hispaniola's location under torture, tells Livesey where the ship is so that the doctor can move it away before the pirates can find it. Moved by the prospect of a youngster facing torture, Livesey tells Jim to escape with him. Jim refuses, saying "I passed my word," adhering to the heroes' ethic of truthfulness even if it involves personal risk. Livesey counters by offering to make Jim's moral standing dependent on his own: "I'll take it on my shoulders, holus bolus, blame and shame, my boy." Jim refuses this dependency, choosing to act as an independent adult like Livesey and his comrades: "'No,' I replied, 'you know right well you wouldn't do the thing yourself--neither you, nor squire nor captain; and no more will I.'"

Several of the other heroes are remarkable for standing by their word, notably Dr. Livesey who, loyal to the Hippocratic Oath, keeps his word to render assistance to the sick, even those he despises such as Billy Bones and the pirates who have captured the stockade. It is mainly lack of loyalty and truthfulness that distinguish Long John Silver from the heroes, who otherwise share many values with him. Silver is not only a chronic liar, but an extremely skilled and convincing one. He pretends so convincingly not to know Black Dog that Jim Hawkins admits that "I would have gone bail for the innocence of Long John Silver." His tales to his fellow mutineers about his early career under Captains England and Flint are probably at least partly fanciful (see historical time frame below). When Jim Hawkins falls into his hands, Silver readily promises to abandon his crew and return to Captain Smollett's orders in exchange for Jim's intervention to spare Silver's life. Then, when he believes Flint's treasure is in his reach, Silver plans (at least according to Jim's perception) to go back on his word, kill Jim, and seize the Hispaniola for himself. Finally, when he finds the treasure gone, Silver again changes sides and betrays his crew. As his last ruse, Silver escapes his captivity with a bag of guineas and disappears.

Temperance versus drunkenness

A strong contrast is constantly drawn between the drunkenness of the pirates (except Silver) and the temperance of the heroes, especially Dr. Livesey. Alcohol undoes many of the villains in Treasure Island. Captain Flint dies from excessive rum drinking. Dr. Livesey warns Billy Bones against drinking further after his first stroke; Bones ignores this warning, suffers a relapse, and dies. Drunkenness leads to the fatal fight between Israel Hands and O'Brien, enabling Jim Hawkins to recapture the Hispaniola. It is strongly implied that the drunken state of the pirates on the island leads to a lack of vigilance, enabling Ben Gunn to kill some of them in their sleep. It is Silver himself who most strongly warns Israel Hands against the consequences of overindulgence in alcohol: "But you're never happy till you're drunk. Split my sides, I've a sick heart to sail with the likes of you! ... You'll have your mouthful of rum tomorrow, and go hang."

Religion versus irreligion

The conflict of piety versus irreligion is mainly developed between Jim Hawkins and Israel Hands on the Hispaniola. Hands is feigning mortal illness, and Jim says that he should pray like a Christian man if he is nearing death. When Hands asks him why, Jim answers heatedly, "For God's mercy, Mr. Hands, that's why." Hands answers at uncharacteristic length, "I never seen good come o' goodness yet. Him as strikes first is my fancy; dead men don't bite; them's my views—Amen, so be it." Also, Jim's faith contrasts with Hands' scepticism regarding an afterlife. When discussing O'Brien, the pirate and mutineer that Hands has murdered, Jim says, "You can kill the body, Mr. Hands, but not the spirit; you must know that already ... O'Brien there is in another world, and maybe watching us." Hands replies, "Well, that's unfort'nate--appears as if killing parties was a waste of time. Howsomever, sperrits don't reckon for much, by what I've seen. I'll chance it with the sperrits, Jim."

Silver's place in the religious conflict is ambiguous. He utters dire imprecations against his shipmates for defacing a Bible, and warns that Dick, the man who yielded his Bible to be defaced, will suffer bad luck for the rest of his life. However, he says this in the context of his men trying to depose him as captain, and his religious threats may be merely tactical, intended to intimidate his opponents. Aside from the Bible incident, Silver shows no obvious inclination toward religion. Many of Silver's men, in turn, take the stigma of defacing the Bible quite seriously, indicating that they have religious feelings and fears of their own . But for both Silver and his men, the idea of inflicting physical damage to the Bible is more frightening than violating the Bible's precepts, suggesting a more ritual than spiritual outlook on religion.

Thrift versus profligacy

The conflict of thrift versus profligacy runs through much of the book. Most of the pirates are unable to hold on to their money; Silver relates that Pew "spends twelve hundred pound in a year, like a lord in Parliament. Where is he now? Well, he's dead now and under hatches, but for two year before that, shiver my timbers! the man was starving. He begged, and he stole, and he cut throats, and starved at that, by the powers!" Ben Gunn exceeds even Pew's lack of foresight; given a thousand pounds of Flint's treasure, he spends and gambles it all away in nineteen days.

According to Silver, these two are wholly typical of pirates: "[W]hen a cruise is done, why, it's hundreds of pounds instead of hundreds of farthings in their pockets. Now the most goes for rum and a good fling, and to sea again in their shirts." Silver himself, again, adheres to the virtue of thrift. Billy Bones manages to hang on to much of his money through the simple expedient of not paying his innkeeper. The heroes are largely thrifty: Jim Hawkins' mother will risk facing pirates rather than let Bones's debt to her go uncollected, Captain Smollett uses his share of the treasure to retire from the sea, and the loyal crewman Gray saves enough money to become a master's mate and raise a family.

Allusions and references

Actual geography

There are a number of islands which could be the real-life inspiration for Treasure Island. One story goes that a mariner uncle had told the young Stevenson tales of his travels to Norman Island in the British Virgin Islands, thus this could mean Norman Island was an indirect inspiration for the book.[10] Nearby Norman Island is a Dead Man's Chest Island, which Stevenson found in a book by Charles Kingsley.

Stevenson said "Treasure Island came out of Kingsley's At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies (1871); where I got the 'Dead Man's Chest' - that was the seed".[11][12] If it was "the seed" for Skeleton Island, the phrase "dead man's chest", the novel in general, or all, remains unclear. Other contenders are the small islands in Queen Street Gardens in Edinburgh, as "Robert Louis Stevenson lived in Heriot Row and it is thought that the wee pond he could see from his bedroom window in Queen Street Gardens provided the inspiration for Treasure Island".[13]

There are a number of Inns which claim to have been the inspiration for places in the book. In Bristol, the Llandoger Trow is claimed to be the inspiration for the Admiral Benbow whilst the Hole in the Wall is claimed to be the Spyglass Tavern. The Pirate's House in Savannah, Georgia is where Captain Flint is supposed to have spent his last days,[14] and his ghost is claimed to haunt the property.[15]

In 1883 Stevenson had also published The Silverado Squatters, a travel narrative of his honeymoon in 1880 in Napa Valley, California. His experiences at Silverado were kept in a journal called "Silverado Sketches", and many of his notes of the scenery around him in Napa Valley provided much of the descriptive detail for Treasure Island.

In May 1888 Stevenson spent about a month in Brielle, New Jersey along the Manasquan River. On the river is a small wooded island, then commonly known as "Osborn Island". One day Stevenson visited the island and was so impressed he whimsically re-christened it "Treasure Island" and carved his initials into a bulkhead. This took place five years after he had completed the novel. To this day, many still refer to the island as such. It is now officially named Nienstedt Island, honoring the family who donated it to the borough.[16][17]

The map of the island bears a vague resemblance to that of the island of Unst in Shetland. The Unst island website claims that Stevenson wrote Treasure Island following a visit to Unst.

Actual history

Allusions to historical pirates and piracies

- Five real-life pirates mentioned are William Kidd (active 1696-1699), Blackbeard (1716–1718), Edward England (1717–1720), Howell Davis (1718–1719), and Bartholomew Roberts (1718–1722).

- The name "Israel Hands" was taken from that of a real pirate in Blackbeard's crew, whom Blackbeard maimed (by shooting him in the knee) simply to assure that his crew remained in terror of him. Allegedly Hands was taken ashore to be treated for his injury and was not at Blackbeard's last fight (the incident is depicted in Tim Powers' novel On Stranger Tides); this alone saved him from the gallows; supposedly he later became a beggar in England.

- Silver refers to a ship's surgeon from Roberts' crew who amputated his leg and was later hanged at Cape Corso Castle, a British fortification on the Gold Coast of Africa. The records of the trial of Roberts' men list one Peter Scudamore as the chief surgeon of Roberts' ship Royal Fortune. Scudamore was found guilty of willingly serving with Roberts' pirates and various related criminal acts, as well as attempting to lead a rebellion to escape once he had been apprehended. He was, as Silver relates, hanged.

- Stevenson refers to the Viceroy of the Indies, a ship sailing from Goa, India (then a Portuguese colony), which was taken by Edward England off Malabar while John Silver was serving aboard England's ship the Cassandra. No such exploit of England's is known, nor any ship by the name of the Viceroy of the Indies. However, in April 1721 the captain of the Cassandra, John Taylor (originally England's second in command who had marooned him for being insufficiently ruthless), together with his pirate partner [18] did capture the vessel Nostra Senhora do Cabo near Réunion island in the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese galleon was returning from Goa to Lisbon with the Conde da Ericeira, the recently retired Viceroy of Portuguese India, aboard. The viceroy had much of his treasure with him, making this capture one of the richest pirate hauls ever. This is likely the event that Stevenson referred to, though his (or Silver's) memory of the event seems to be slightly confused. The Cassandra is last heard of in 1723 at Portobelo, Panama, a place that also briefly figures in Treasure Island as "Portobello".

- The preceding two references are inconsistent, as the Cassandra (and presumably Silver) was in the Indian Ocean during the entire time that Scudamore was surgeon on board the Royal Fortune, in the Gulf of Guinea.

- One actual pirate who buried treasure on an island was William Kidd on Gardiners Island. The booty was recovered by authorities soon afterwards.[19]

Other allusions

- 1689: A pirate whistles "Lillibullero" (1689).

- 1702: The Admiral Benbow inn where Jim and his mother live is named after the real life Admiral John Benbow (1653–1702).

- 1733: Captain Flint, who may or may not have been fictional, died in the town of Savannah, Georgia, founded in 1733.

- 1745: Doctor Livesey was at the Battle of Fontenoy (1745).

- 1747: Squire Trelawney and Long John Silver both mention "Admiral Hawke", i.e. Edward Hawke, 1st Baron Hawke (1705–1781), promoted to Rear Admiral in 1747.

- 1749: The novel refers to the Bow Street Runners (1749).

Possible influences

- Squire Trelawney may have been named for Edward Trelawney, Governor of Jamaica 1738-1752.

- Dr. Livesey may have been named for Joseph Livesey (1794–1884), a famous 19th-century temperance advocate, founder of the tee-total "Preston Pledge". In the novel, Dr. Livesey warns the drunkard Billy Bones that "the name of rum for you is death."[20][21]

Historical time frame

Stevenson deliberately leaves the exact date of the novel obscure, Hawkins writing that he takes up his pen "in the year of grace 17--." However, some of the action can be connected with dates, although it is unclear if Stevenson had an exact chronology in mind. The first date is 1745, as established both by Dr. Livesey's service at Fontenoy and a date appearing in Billy Bones's log. Admiral Hawke is a household name, implying a date later than 1747, when Hawke gained fame at the Battle of Cape Finisterre and was promoted to Admiral, but prior to Hawke's death in 1781.

Another hint, though obscure, as to the date is provided by Squire Trelawney's letter from Bristol in Chapter VII, where he indicates his wish to acquire a sufficient number of sailors to deal with "natives, buccaneers, or the odious French". This expression suggests that Great Britain was, at that time, at war with France; e.g., during the War of the Austrian Succession from 1740 to 1748, or the Seven Years' War from 1756 to 1763.

Stevenson's map of Treasure Island includes the annotations Treasure Island Aug 1 1750 J.F. and Given by above J.F. to Mr W. Bones Maste of ye Walrus Savannah this twenty July 1754 W B. The first of these two dates is likely the date at which Flint left his treasure at the island; the second, just prior to Flint's death. As Flint is reliably reported to have died at least three years before the events of the novel (the length of time that Ben Gunn was marooned), it cannot take place earlier than 1757 and still be consistent with the map. The events of Treasure Island would therefore seem to have taken place no earlier than 1757. As the schooner Hispaniola docks peacefully at a port in Spanish America — where it even finds a British man-of-war — at the end of the story, it must also take place before 1762, when Spain joined the Seven Years' War against Great Britain. The evidence above therefore implies a date between 1757 and 1762.

This range of dates, however, contradicts Long John Silver's account of himself, as given to Dick while Jim Hawkins listened in the apple barrel. Silver claims to be fifty years old, which would place his birth no earlier than 1707; and both Silver and Israel Hands, who had been in Flint's crew together, claim to have had experience on the sea (presumably as pirates) for thirty years prior to their arrival at Treasure Island, i.e. since about 1727. However, Silver claims to have sailed "First with England, then with Flint", which pushes the beginning of his career to some time before 1720, the date of Captain Edward England's death, implying a longer career at sea than thirty years. Silver also says that the surgeon who amputated his leg was hanged with Roberts's crew at Corso Castle: this would mean he has been disabled at least since 1722, at an age no greater than 15—-an age incompatible with his holding as significant an office as quartermaster under Captain Flint, or with being a crewman under England who was senior enough, and served long enough, to have "laid by nine hundred [pounds] safe".

As noted under Actual history, some of the people and events Silver claims to have witnessed were on opposite sides of Africa at the same time, and Silver's assignments of names and places are not entirely accurate. Silver's stories, then, may be no more reliable than his claim to have lost his leg while serving under Admiral Hawke, and containing inconsistencies which his audience were too ignorant to notice. Silver must either be closer to sixty than fifty, or his stories of the pirates England and Roberts are fabrications, retellings of stories he had heard from other pirates, into which he has inserted himself-—which would account for their inconsistencies.

Sequels and prequels

- In the novel Peter Pan (1911) by J. M. Barrie, it is said that Captain Hook is the only man the old Sea-Cook ever feared. Captain Flint and the Walrus are also referenced.

- Author A. D. Howden Smith wrote a prequel, Porto Bello Gold (1924), that tells the origin of the buried treasure, recasts many of Stevenson's pirates in their younger years, and gives the hidden treasure some Jacobite antecedents not mentioned in the original.

- Author H. A. Calahan wrote a sequel Back to Treasure Island (1935). Calahan argued in his introduction that Robert Lewis Stevenson wanted to write a continuation of the story.

- Author R. F. Delderfield wrote The Adventures of Ben Gunn (1956) which follows Ben Gunn from parson's son to pirate and is narrated by Jim Hawkins in Gunn's words.

- Author Leonard Wibberley wrote a sequel, Flint's Island (1972).

- Author Denis Judd wrote a sequel, Return to Treasure Island (1978).

- Author Bjorn Larsson wrote a sequel, Long John Silver (1999).

- Author Frank Delaney wrote a sequel, The Curse of Treasure Island (2001) using the pseudonym "Francis Bryan".

- Author Roger L. Johnson wrote Dead Man's Chest:The Sequel to Treasure Island (2001).

- Writer Xavier Dorison and artist Mathieu Lauffray started the French graphic novel in four books Long John Silver in 2007. The final books still have to be published in France.

- Author John Drake wrote a prequel, Flint & Silver (2008)[22] Two more books followed: Pieces of Eight (2009) and Skull and Bones (2010).

- Author John O'Melveny Woods wrote a sequel, Return to Treasure Island (2010).

References in other works

- German metal band Running Wild, who are known for their lyrics on piracy, wrote an 11 minute epic on the story on their 1992 album Pile of Skulls.

- Long John Silver and Treasure Island make an appearance in the 1994 film, The Pagemaster.

- Spike Milligan wrote a parody, Treasure Island According to Spike Milligan (2000).

- Avi, author of The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, wrote the foreword to the 2000 edition of Treasure Island from Alladin Classics.

- In LucasArts' The Curse of Monkey Island, the main character Guybrush Threepwood sings a commercial jingle about "Silver's Long Johns" (they breathe!) in an attempt to be the fourth member of a barbershop quartet.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl, Hector Barbossa names his pet monkey after Jack Sparrow, a captain he mutinied against. This may have been inspired by Silver naming his parrot Captain Flint.

- According to the screenwriters' commentary on the DVD of Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, the captain killed by an East India Trading Company official early in the movie is Jim Hawkins' lost father. This is, however, contrary to the original book: Jim Hawkins' father died at the Admiral Benbow Inn, in the company of Jim and his mother, in chapter three. Dead Man's Chest also makes use of a "black spot".

- In Dutch author Reggie Naus' children's novel De schat van Inktvis Eiland ("The treasure of Squid Island") (2008), the main character's last name is Stevenson. Though the plot is unrelated to Stevenson's novel, the pirates in this book brush shoulders with characters from Treasure Island. Another character in the novel, the quartermaster Walter Gunn, is Ben Gunn's older brother. The song "Fifteen men on a dead man's chest" features frequently in the book. The writer is a big fan of Stevenson's book and included these references in tribute.

- In the Swallows and Amazons series by Arthur Ransome the Amazons' (Blacketts') Uncle Jim has the nickname of Captain Flint and a parrot.

- Alan Coren wrote an article in Punch, entitled "A Life on the Rolling Mane", parodying Treasure Island to adapt it to the National Hairdressers' Association's campaign to stamp out "pirate barbers". Notable lines are Bald Pew's "Remember the days of the old clippers?" and Hawkins' memories of the "boom of the scurf".

- The seafood restaurant chain "Long John Silver's" was named after the main villain.

- In the Zoobilee Zoo episode "Is There a Doctor in the House?", three of the Zoobles play three of the characters in Treasure Island, with Bravo Fox playing the main villain.

- In the animated series Fox's Peter Pan and the Pirates, based in part on the original Peter Pan stories, Captain Flint is referenced in the episode Peter on Trial, as Captain Hook is stated as being the only man that a pirate named Barbecue is stated to fear, with the following statement being that 'Even Flint feared Barbecue', referring to Captain Flint from Treasure Island. In the same episode, Flint is referenced as being the pirate who supposedly conceived of the idea of pirates putting members of their crew, or their prisoners as the case might be, on trial in an event called a 'Captain's mass'.

Adaptations

Film and TV

There have been over 50 movie and TV versions made.[23] Some of the notable ones include:

Film

- 1920 - Treasure Island - A silent version starring Shirley Mason.

- 1934 - Treasure Island - Starring Jackie Cooper and Wallace Beery. An MGM production, the first sound film version.

- 1937 - Treasure Island - A loose Soviet adaptation starring Osip Abdulov and Nikolai Cherkasov, with a score by Nikita Bogoslovsky.

- 1950 - Treasure Island - Starring Bobby Driscoll and Robert Newton. Notable for being Disney's first completely live action film. A sequel to this version was made in 1954, called Long John Silver.

- 1971 - Treasure Island - A Soviet (Lithuanian) film starring Boris Andreyev, with a score by Alexei Rybnikov.

- 1971 - Animal Treasure Island - An anime film directed by Hiroshi Ikeda and written by Takeshi Iijima and Hiroshi Ikeda with story consultation by famous animator Hayao Miyazaki. This version replaced several of the human characters with animal counterparts.

- 1972 - Treasure Island - Starring Orson Welles.

- 1985 - L'Île au trésor

- 1987 - L'isola del tesoro - Italian / German SF adaptation AKA Treasure Island in Outer Space starring Anthony Quinn as Long John Silver.

- 1988 - Treasure Island (1988 animated film) - A critically acclaimed Soviet animation film in one part.

- 1990 - Treasure Island - Starring Charlton Heston

- 1996 - Muppet Treasure Island

- 1999 - Treasure Island - Starring Kevin Zegers and Jack Palance.

- 2002 - Treasure Planet. A Disney animated version set in space, with Long John Silver as a cyborg and many of the original characters re-imagined as aliens except for Jim and his family.

- 2006 - Pirates of Treasure Island - A direct-to-DVD film by The Asylum, which was released one month prior to Dead Man's Chest.

- 2007 - Die Schatzinsel. A loosely adapted version, in German, starring German and Austrian actors, of the original novel.

TV

- 1955 - The Adventures of Long John Silver, 26 episodes shot at Pagewood Studios, Sydney, Australia filmed in full colour and starring Robert Newton

- 1964 - Mr. Magoo's Treasure Island, a 2 part episode of the cartoon series The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo (1964) was based on the novel, with Mr. Magoo in the role of Long John Silver.

- 1966 - "Die Schatzinsel" - German-French co-production for German television station ZDF.

- 1968 - Treasure Island - BBC series of nine 25 minute episodes starring Peter Vaughn.

- 1977 - Treasure Island - Starring Ashley Knight and Alfred Burke.

- 1978 - Treasure Island (Takarajima) - A Japanese animated series adapted from the novel.

- 1982 - Treasure Island - The best known Soviet adaptation of the book, in three parts, starring Oleg Borisov as John Silver

- 1990 - Treasure Island - Starring Christian Bale, Charlton Heston, Christopher Lee and Pete Postlethwaite. A made for TV film written, produced and directed by Heston's son, Fraser C. Heston.

- 1993 - The Legends of Treasure Island - An animated series loosely based on the novel, with the characters as animals.

- 1995 - In the Wishbone (TV series) episode "Salty Dog", Wishbone explores the story in a children's adapted version.

There are also a number of Return to Treasure Island sequels produced, including a 1986 Disney mini-series, a 1992 animation version, and a 1996 and 1998 TV version.

Theatre and radio

There have been over 24 major stage and radio adaptations made.[24] The number of minor adaptations remains countless.

- Orson Welles broadcast a radio adaptation via Mercury Theatre on July 1938; half in England, half on the Island; omits "My Sea Adventure"; music by Bernard Herrmann; Available online.

- In 1947, a production was mounted at the St. James's Theatre in London, starring Harry Welchman as Long John Silver and John Clark as Jim Hawkins.

- For a time, in London there was an annual production at the Mermaid Theatre, originally under the direction of Bernard Miles, who played Long John Silver, a part he also played in a television version. Comedian Spike Milligan would often play Ben Gunn in these productions.

- Pieces of Eight, a musical adaptation by Jule Styne, premiered in Edmonton, Alberta, in 1985.

- The Henegar Center for the Arts in downtown historic Melbourne, Florida ran an adaptation in August 2009.

- The story is also a popular plot and setting for a traditional pantomime where Mrs. Hawkins, Jim's mother is the dame

Music

- The Ben Gunn Society album released in 2003 presents the story centered around the character of Ben Gunn, based primarily on Chapter XV "Man of the Island" and other relevant parts of the book.

- Treasure Island song from Running Wild's album named Pile of Skulls (1992). The pirate power metal thematic of the band is well placed in this song, telling the novel's story.

Software

A computer game based loosely on the novel was issued by Commodore in the mid 1980s for the Plus/4 home computer, written by Greg Duddley. A graphical adventure game, the player takes the part of Jim Hawkins travelling around the island despatching pirates with cutlasses before getting the treasure and being chased back to the ship by Long John Silver. A catchy tune is included.

Footnotes

- ↑ Porterfield, Jason. "Treasure Island and the Pirates of the 18th Century". pp. 7 et seq.. http://books.google.com/books?id=kJ_hrsS9GwoC&pg=PA7.

- ↑ Cordingly, David (1995) Under the Black Flag New York: Random House, p. 3

- ↑ Letley, pp.vii - viii (Stevenson, however, claims it was his map, not Lloyd's, that prompted the book)

- ↑ Yardley, Jonathan, Stevenson's 'Treasure Island': Still Avast Delight, Washington Post, April 17, 2006

- ↑ Guga Books at Octavia & Co. Press

- ↑ Paine, Ralph Delahaye (1911) The book of buried treasure; being a true history of the gold, jewels, and plate of pirates, galleons, etc., which are sought for to this day. New York: Macmillan. via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Cordingly, David (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates. Page 6-7.

- ↑ Cordingly, David (1995) Under the Black Flag: the romance and reality of life among the pirates; p. 7

- ↑ Stevenson, R.L. p 34: "...{Pew} made another dash, now utterly bewilidered, right under the nearest of the coming horses. The rider tried to save him, but in vain. Down went Pew with a cry that rang high into the night; and the four hoofs trampled and spurned him and passed by. He fell on his side, then gently collapsed upon his face, and moved no more."

- ↑ "Where's Where" (1974) (Eyre Methuen, London) ISBN 0-413-32290-4

- ↑ David Cordingly. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. ISBN 0-679-42560-8.

- ↑ Robert Louis Stevenson. "To Sidney Colvin. Late May 1884", in Selected Letters of Robert Louis Stevenson. Page 263.

- ↑ "Brilliance of 'World's Child' will come alive at storytelling event", (Scotsman, 20 October 2005).

- ↑ The Pirates House history

- ↑ Ghost of Captain Flint

- ↑ Richard Harding Davis (1916). Adventures and Letters of Richard Harding Davis. See page 5 from Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ [1] History of Brielle

- ↑ Olivier Levasseur

- ↑ Adams, Cecil The Straight Dope: Did pirates bury their treasure? Did pirates really make maps where "X marks the spot"? October 5, 2007

- ↑ Reed, Thomas L. (2006). The Transforming Draught: Jekyll and Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Victorian Alcohol Debate. Pages 71-73.

- ↑ Hothersall, Barbara. "Joseph Livesey". http://www.fulwood.org.uk/magazine/fmcmag/2003/harvest/livesey/joseph_livesey.php. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ↑ Greene & Heaton. John Drake's Flint & Silver.

- ↑ Dury, Richard. Film adaptations of Treasure Island.

- ↑ Dury, Richard. Stage and Radio adaptations of Treasure Island.

References

- Cordingly, David (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates. ISBN 0-679-42560-8

- Letley, Emma, ed. (1998). Treasure Island (Oxford World's Classics). ISBN 0-19-283380-4

- Reed, Thomas L. (2006). The Transforming Draught: Jekyll and Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson, and the Victorian Alcohol Debate. ISBN 0-7864-2648-9

- Watson, Harold (1969). Coasts of Treasure Island;: A study of the backgrounds and sources for Robert Louis Stevenson's romance of the sea. ISBN 0-8111-0282-3

External links

Editions

- Treasure Island at Project Gutenberg

- Treasure Island, scanned and illustrated books at Internet Archive. Notable editions include:

- Treasure Island, 1911 Scribner's, illustrated by N. C. Wyeth. See also alternate edition (better quality scan, some images missing).

- Treasure Island, 1915 Harpers, illustrated by Louis Rhead.

- Treasure Island, 1912 Scribner's "Biographical Edition", includes essays by Mr and Mrs Stevenson.

- Treasure Island, 1911 Ginn and Company, lengthy introduction and notes by Frank Wilson Cheney Hersey (Harvard University).

- Treasure Island, with an Introduction and notes by Franklin T Baker (Columbia University, 1909). Fully annotated online.

- Treasure Island, audiobook from Librivox

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scottish author